OLED (Organic Light-Emitting Diode) is a light-emitting technology in which organic semiconductor layers emit light directly when an electric current is applied. Unlike LCDs, OLEDs do not require a separate backlight, and unlike conventional LEDs, they emit light uniformly across a surface rather than from a point source. This enables thin, flexible, self-emissive light and display applications.

In simple terms, OLED produces light at the surface of organic materials, allowing screens and light sources to be thinner, more flexible, and self-illuminating.

OLED is most commonly associated with smartphone screens and televisions, yet the technology itself extends far beyond displays. At its core, OLED is a method of generating light directly at the surface of a material. How that light is produced, shaped, and integrated depends largely on how the OLED is manufactured.

As OLED applications expand into packaging, wearables, safety equipment, and ambient interfaces, the distinction between display-grade OLEDs and printed OLED light sources becomes increasingly important. This article explains what OLED is, how it works, the main types of OLED technologies, and why printed OLEDs enable use cases that conventional OLED manufacturing cannot support.

An OLED consists of multiple ultra-thin organic layers positioned between two electrodes. When voltage is applied, electrical charges recombine within the organic layers and release energy in the form of light. Because light is generated directly at the emission layer, OLEDs are self-emissive and do not rely on reflection or external illumination.

This operating principle applies to all OLED technologies. What differs significantly is how the organic layers are deposited, encapsulated, and electrically connected. These manufacturing decisions determine whether an OLED becomes a high-resolution display or a flexible surface light source.

OLED is not a single technology but a family of manufacturing approaches. The most relevant distinction lies in how the organic layers are applied and structured.

This distinction matters because manufacturing constraints define application boundaries. Display-grade OLEDs prioritize pixel density, brightness, and refresh rate. Printed OLEDs prioritize flexibility, thinness, uniform emission, and integration into non-electronic materials.

Printed OLEDs are OLED light sources manufactured using printing techniques rather than vacuum evaporation. Instead of producing pixel-based displays, printed OLEDs create continuous light-emitting surfaces.

They are typically:

Printed OLEDs are designed for illumination and signaling rather than image rendering. Their primary role is to deliver soft, readable light cues that can be integrated into materials such as paper, textiles, or flexible polymers.

Printed OLED manufacturing replaces vacuum-based deposition with solution-based printing. Organic materials are deposited layer by layer onto flexible substrates, followed by encapsulation to protect the organic layers from moisture and oxygen.

From a manufacturing perspective, this shifts complexity rather than eliminating it. Printing introduces challenges related to layer consistency, material stability, encapsulation durability, electrical interface reliability, and production yield. Each of these factors influences achievable lifetimes, form factors, and operating conditions.

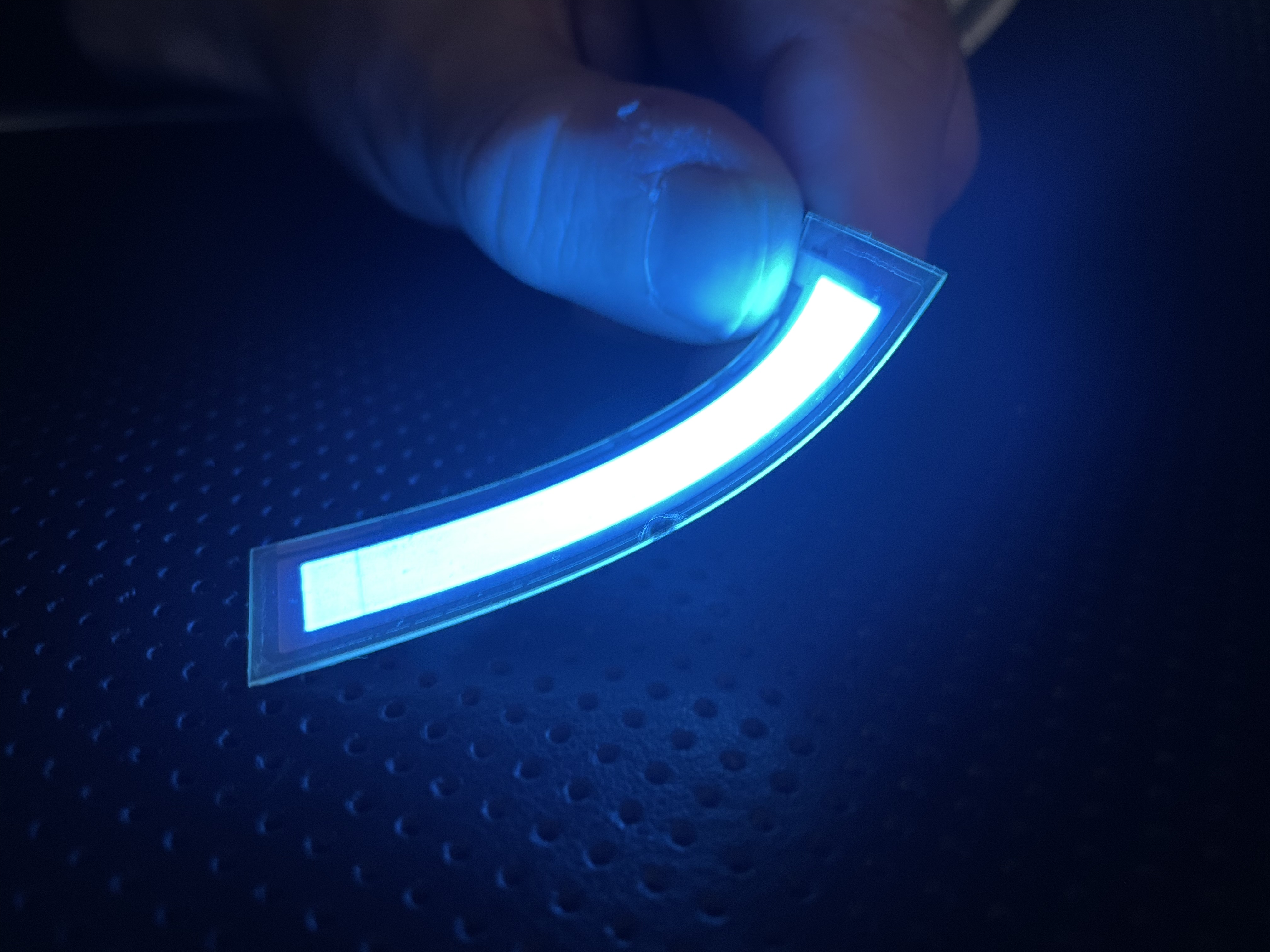

Printed manufacturing also enables free-form printed OLED elements, where the light-emitting surface can be shaped to follow functional or design constraints rather than rigid rectangular formats. This capability is essential for applications where space, curvature, or material compatibility limit conventional electronics.

Printed OLEDs are often compared directly to display-grade OLEDs, yet they are optimized around fundamentally different performance criteria. While display OLED manufacturing focuses on resolution, pixel density, and refresh rate, printed OLED manufacturing prioritizes uniform surface emission, mechanical flexibility, and compatibility with non-electronic substrates.

Printing organic layers introduces a distinct set of manufacturing considerations. Layer uniformity must be maintained across flexible materials, encapsulation must protect against environmental exposure, and electrical stability must be ensured over repeated handling or bending. These constraints shape design decisions from the earliest development stages.

As a result, printed OLEDs are not intended to replicate the performance of displays. Instead, they enable light-emitting surfaces that function reliably in environments where traditional OLED displays or rigid lighting components are unsuitable.

In packaging applications, printed OLEDs must be evaluated not only for optical performance but also for environmental compatibility. Substrate choice, encapsulation materials, and end-of-life separation influence whether illuminated packaging can align with recycling systems.

Printed OLEDs enable thinner constructions and lower overall material mass compared to rigid lighting components. However, integration decisions must be made early in the design process to avoid conflicts with downstream recycling or disposal requirements.

Brightness is frequently used as a shorthand metric when comparing light technologies. In human-facing applications, excessive brightness can reduce legibility, comfort, and recognition.

Printed OLEDs are typically designed to operate at lower luminance levels, emphasizing visibility rather than illumination. Uniform surface light is detected more reliably in peripheral vision than intense point sources, particularly in environments with inconsistent ambient lighting. For this reason, OLED performance must be evaluated in context, not by brightness alone.

As OLED technology moves beyond displays, packaging and wearables represent two of the most demanding environments. Both require light sources that are thin, durable, energy-efficient, and readable under variable lighting conditions.

Printed OLEDs address these constraints by providing stable surface illumination without introducing bulk or rigid components. In packaging, this supports visibility and signaling without altering form factors. In wearables, it enables active visibility while preserving flexibility and comfort.

Companies such as Inuru focus specifically on printed OLED manufacturing for these application categories, where production constraints matter as much as optical performance.

These structural differences explain why OLEDs are increasingly used where human-centric visibility matters more than maximum brightness.

Many explanations of OLED focus on physics or display history. In real-world applications, manufacturing method determines achievable form factor, durability, energy consumption, environmental compatibility, and scalability.

Without understanding how an OLED is manufactured, it is impossible to assess whether it is suitable for packaging, wearables, or safety-critical environments.

The answers below are updated over time as manufacturing methods and applications evolve.

Is OLED better than LED?

OLED and LED serve different purposes. OLED provides uniform surface emission and thin integration, while LEDs deliver higher point brightness and directional light.

Can OLED be flexible?

Yes. Printed OLEDs and some flexible OLED displays can bend and conform depending on substrate and encapsulation design.

How long do OLEDs last?

Lifetime depends on materials, operating conditions, and brightness levels. Printed OLEDs used for low-intensity signaling typically operate within stable lifetime ranges suitable for packaging and wearable applications.

Do printed OLEDs generate heat?

Printed OLEDs operate at low power densities and generate minimal heat during normal operation. Thermal management is usually not a limiting factor in surface-light applications.

Can printed OLEDs be shaped into custom forms?

Yes. One advantage of printed OLED manufacturing is the ability to create free-form light-emitting geometries that follow functional or design constraints rather than fixed rectangular shapes.

OLED is best understood not as a single product category, but as a family of light-emitting technologies shaped by manufacturing choices. Printed OLEDs expand what OLED can be used for by prioritizing flexibility, surface emission, and integration over resolution.

As OLED applications move further into physical environments—such as packaging, wearables, and safety systems—the ability to manufacture light sources that respect real-world constraints becomes the defining factor. Understanding OLED at the manufacturing level is therefore essential to understanding where the technology truly fits.

If you’re evaluating OLED use beyond traditional displays, contact us to discuss feasibility, constraints, and manufacturing considerations.

Last updated: December 2025

SOURCES:

(1)https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/organic-light-emitting-diode

(3)https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-43014-7

(4)https://crimsonpublishers.com/boj/pdf/BOJ.000527.pdf

(5)https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abl8798

(6)https://advanced.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/adfm.202100151

(7)https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0079642520301249